Carbon compounds are arguably the most infamous of all the greenhouse gases, but they are not the only chemical offenders deserving of concern. In fact, nitrogen is capable of causing severe damage to the environment as well. This simple element, harmless when safely bound in pairs in Earth's atmosphere, becomes extremely volatile when generated by human activities. When combined with other elements such as hydrogen and oxygen, so-called reactive nitrogen compounds wreak havoc on the environment by way of soil acidification, smog production, and the release of excess chemical nutrients into the environment, a process known as eutrophication.

Although reactive nitrogen is also produced in nature, human methods of mass food production have outstripped even the most prolific nitrogen-producing ecosystems. Since the 1970s, we humans have driven greater numbers of our species up the food chain by consuming more animal protein and crops such as legumes than ever before, all the while releasing higher and higher levels of reactive nitrogen into the environment around us.

Nitrogen, in this sense, is both a boon and a curse.

Therefore, the question driving scientists is one of balance: How can we humans be responsible about our nitrogen emissions while simultaneously advancing the world's societies?

Enter the Nitrogen Footprint Project, a venture spearheaded by the University of Virginia and funded by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) that aims to help others analyze and decrease their nitrogen emissions. Over the last year, Brown University and five other institutions have worked with a team of UVA scientists, including lead researcher James Galloway, project manager Elizabeth "Izzy" Castner (Brown'14), and the Footprint model's designer Alley Leach (now at UNH) to derive a clearer picture of their own institutional footprint.

The culmination of this first round of calculations occurred late last month, at a three-day conference hosted by the Institute at Brown for Environment and Society. IBES Fellow Meredith Hastings and Postdoctoral Fellow Becca Ryals, who have been working on the project since its inception, presented Brown University's results.

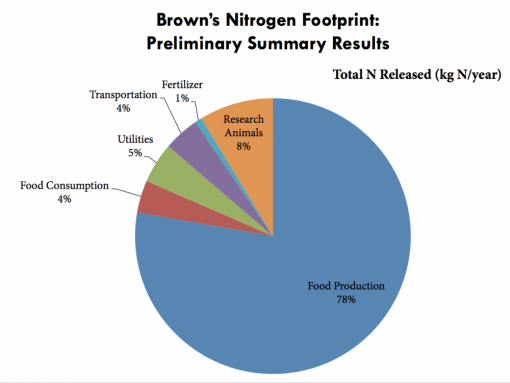

Their analysis was enlightening. Food production is far and away the largest contributor to Brown's nitrogen footprint (78%), releasing almost 100,000 kg of nitrogen into the environment each year. Moreover, almost three-quarters of these emissions are due to the processing of and waste from animal protein sources such as meat, dairy, and eggs.

Their analysis was enlightening. Food production is far and away the largest contributor to Brown's nitrogen footprint (78%), releasing almost 100,000 kg of nitrogen into the environment each year. Moreover, almost three-quarters of these emissions are due to the processing of and waste from animal protein sources such as meat, dairy, and eggs.

The care and keeping of research animals was found to contribute 8% of the annual nitrogen released by the University. This source was greater than food consumption (4%) or utilities (5%), which are principally powered by natural gas. Brown's transportation sector (4%) reported data with the most uncertainties regarding nitrogen emissions, mainly due to unknowns in the University's commuting population. The last 1% of emissions were contributed by fertilizer.

The results were based on records from fiscal year 2015. Brown undergraduate Allison Cluett assisted with data collection.

Hastings and Ryals will continue to work with nitrogen-producing sectors at Brown with an eye toward reducing the University's nitrogen footprint even further. Local initiatives such as the Real Food Challenge and composting of food waste, together with an increase in the use of organic products and number of vegetarian offerings at campus dining facilities, may help to cut the reactive nitrogen emissions of food production. Composting animal bedding after use and more frequently employing smaller creatures such as fish could help to reduce emissions from the research animal sector. Future sustainability initiatives should ideally keep these and other recommendations in mind.

Want to learn more about your own, personal Nitrogen Footprint? Try out the team's online calculator.

The Nitrogen Footprint Project is sponsored by the EPA Sustainable and Healthy Communities Program.