Over time, the settlers influenced many fundamental areas of "Nuragic" life, giving rise to new ways of building homes, farming land, and cooking food—permanently altering the Sardinian culture and countryside in subtle ways, and preserving it in others.

Thousands of years later, archaeologist Peter van Dommelen and his team are retracing these foreign encounters in an effort to better understand the changes wrought by colonialism in Sardinia, on both local peoples and their land.

Colonialism and culture

Van Dommelen, a native of the Netherlands, has been conducting research in Sardinia for over 25 years. His fascination with the region stems from its pivotal role in what he calls the "formative moments of the ancient world": the arrival of Phoenicians from the Levant, the establishment of Carthage, the Punic Wars, and the subsequent sprawl of the Roman Empire.

But his efforts are also based in a desire to shed light on the ordinary people of classical antiquity; that is, those who were not crafting famous works of art or pioneering influential architecture—who, instead, whiled away their days engaging in relatively quiet yet vital tasks like animal husbandry, cooking, or producing goods and services. For van Dommelen, unearthing the past represents a way to give voice to these so-called "people without history."

Colonial encounters, like the ones that occurred in Sardinia beginning around 900 BCE, only serve to enrich this study. Indeed, archaeology reveals much about the ways in which foreign influences altered the lives of everyday people on the island.

"You see the culture changing," explains van Dommelen. "People start eating in different ways. They change their pottery, their utensils, everything—their way of life, their way of burying their dead."

At excavation sites in Sardinia, van Dommelen and his team have uncovered proof of colonial influences in the form of Phoenician kitchen wares, Greek pottery, and large, Middle Eastern-style bread ovens; however, the researchers have also unearthed large numbers of discarded cattle bones alongside their other finds, revealing evidence of a food source that was preferred in the local, Nuragic diet. Indeed, despite the changes so often wrought by colonial settlers, van Dommelen explains that some local traditions usually persist. He and his team are fascinated by the way that colonial influences mix with native practices to create an entirely new culture.

"What we're basically looking at is a community that, by the 5th or 4th century BCE or so, is still eating cattle as their ancestors had done," explains van Dommelen, "but because of all their new connections, they are eating their beef on a Middle Eastern flatbread, and enjoying it from plates that are Phoenician-style."

"In a way it's comparable to what you see in our society, in cities, where you can go from pizza to Indian to Greek on one street, and find them including native ingredients like corn and turkey," he says.

Connected to the land

It isn't just people that change in the face of foreign influence; the earth beneath their feet changes as well. The Institute has sponsored an interdisciplinary branch of van Dommelen's project in which the team is examining the way that land use, geology, and soil composition changed along with the ambient culture in Sardinia.

"It's clear that agricultural techniques are changing," he says. "After colonization there are simply more farms out in the countryside, so it's actually a greater intensity of land use and of agricultural production."

Van Dommelen is no stranger to the ways that humans have altered their lived environments over the millennia. From silty marshland forged due to damming of a large river around 500 BCE to ancient ice cores that show evidence of pollution during the times of the Romans, archaeology clearly reveals the historical human influence on both local and global ecosystems.

"That's where the intersection with IBES is," he explains. "People in the past engaged with physical landscapes and have left traces, built farms, and were working lands—they were transforming their environment."

Heritage matters

In the Sardinian village of San Vero Milis, van Dommelen's team works closely with farmers who are responsible for tending the same fields as their ancestors did, gathering information about the way they use the land today and describing the relics that have been uncovered in the area.

"It was very interesting, the survey that we did with the IBES funds, talking with peasants and farmers around the area," he says. "They were very interested to hear what could be down there in something that they now think of as their best land. That's very rewarding."

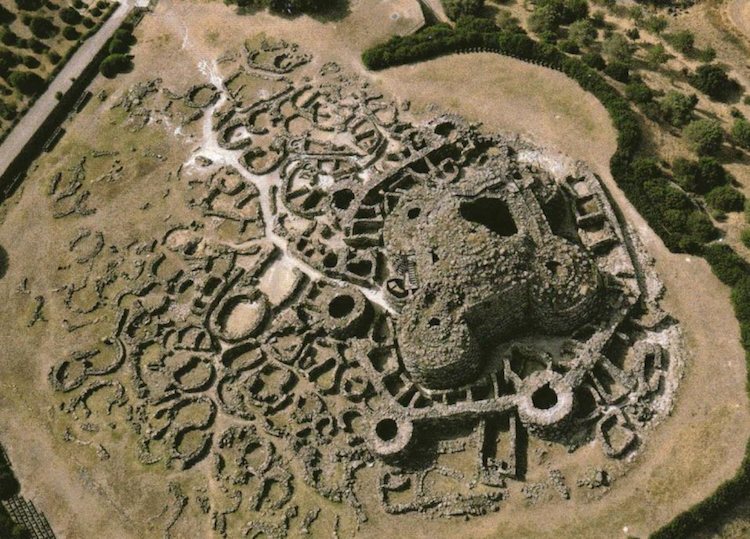

Thanks in part to an enormous stone nuraghe just outside of town, locals have a keen interest in their own heritage and history. In this way, van Dommelen's research has become somewhat of a community endeavor.

In fact, the village itself has facilitated many of the logistics necessary to the project at large: securing the excavation permit, hiring a staff archaeologist, maintaining a local museum and accompanying research infrastructure, and providing a safe space for van Dommelen and his team to store their tools and equipment. In the summertime, local amateurs, University students, and high school students even get their hands dirty by helping with the excavation.

In honor of the locals' hard work and participation, van Dommelen, his Sardinian counterpart Alfonso Stiglitz, and the rest of the team present their findings each year at the end of the field season, at an event that typically attracts 100 or more community members. Today's Sardinians are eager to learn more about their forbears' traditions, livelihoods, and unique cultural relationship to the nearby giant stone nuraghe.

"The thing that they repeat all the time is that they're so grateful that someone is really looking at their monument," van Dommelen says. "That's how they regard it: ‘It's our monument, it's our ancestors and past.' And we're coming up with all these details about the past and it's basically bringing it back to life."

"That's where I think archaeology is important," he continues, "because it helps people to create a relationship to their living environment. And the living environment is not just the environment that's created by the city or the state; it's also the past that you relate to."

"We don't live in a vacuum," he adds. "We go somewhere, but also we come from somewhere. There are plenty of single-narrative, nationalist, or otherwise-motivated pasts that are being promoted, but archaeology actually reveals that the past is never simple."

Indeed, after centuries of outsiders reshaping the local culture and heritage, Sardinia has become a melting pot of many different influences: from its indigenous Bronze Age roots and subsequent Middle Eastern influences to the Roman Empire and the modern Italian state. The historical marriage of cultures on this small island is not linear or straightforward, but van Dommelen takes this fact in stride.

"Archaeology—seeing those direct remains—is often very messy, and it confronts you directly with the messiness," he says. "Well, life isn't straightforward and neat; it tends to be messy. And that's what I think you see in the past as well."

Van Dommelen is Director of the Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the Ancient World. He is the Joukowsky Family Professor in Archaeology, a Professor of Anthropology and Italian Studies, and an IBES fellow.