The course, Humans, Nature, and the Environment: Addressing Environmental Change in the 21st Century attracts a potpourri of undergraduates. More colloquially known as "ES 11," the course draws Brunonians of all class years and from a variety of disciplines, each seeking a way to learn more about the field of environmental studies while simultaneously becoming more involved in the local community. The time- and labor-intensive course is cross-listed in the University's Engaged Scholars Program; and as King explains, the categorization is well-earned.

"It's probably one of the most engaged courses at the University," she says. "All of the [students' assignments], for the most part, have an engaged option. Even the final paper and or project can involve working with a community partner."

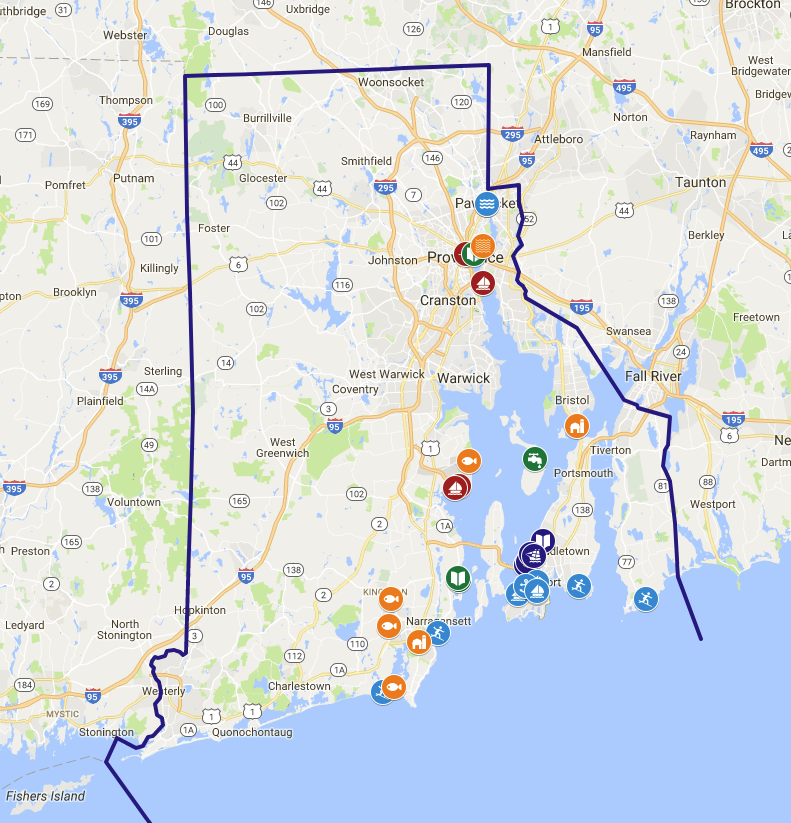

These community partners take many forms; in recent years, students have paired up with local farms, non-profits, advocacy groups, and city offices to contribute in ways that are customized to the real-world needs of the organization—whether that means digging into archives, mapping the state's "blue economy" with GIS technology, building a portable chicken coop, or convincing Brown's dining office to partner with fishermen in order to offer more sustainable dietary options.

And although students learn plenty from their partnerships, in many ways community groups are the real beneficiaries.

"When Dawn King's students are done, the community benefits," says Julius Kolawole, President of the African Alliance of RI, a long-time partner to King's students. "Whatever they do, the community gets benefits. That aspect of what they do is what I refer to as the ‘community practice'. In other words, they leave something behind."

"College can be such an insular experience," adds Tess Brown-Lavoie of Sidewalk Ends Farm, another local organization that has hosted many ES11 students over the years. "There is so much going on on campus and in classrooms to captivate a student's mind and time, but we consistently hear that trips out to the farm help initiate valuable relationships with the greater Providence community."

This sentiment is echoed by many of King's former students, especially those who currently act as Teaching Assistants for the class.

"Brown, in so many ways, can act really siloed from the rest of Providence and the rest of Rhode Island," says Thomas Culver ‘17. "But these engaged projects really force a part of the Brown community to engage with part of the community outside and form meaningful long-term connections."

"I think that this class does a really successful job at making students think about their role in the community," adds Allyson Masunaga Goto'18. "How they can help in a really meaningful way that isn't just surface-level stuff, and that really gets to the deep roots of the problems that we talk about in class."

Although the course itself is designed to be introductory, its immense breadth encourages non-concentrators to cultivate deep-rooted environmental perspectives, and to make connections within their own disciplines.

"It is a survey class, but you hit on different angles," explains Kaori Nagase ‘17. "You get a little bit of electoral politics or a little bit of science or a little bit of econ. And even if you don't end up concentrating in Environmental Studies or Science, many students take classes in those respective departments, or choose to explore environmental issues through class assignments, papers, and projects."

Moreover, the course encourages students who do concentrate in ES to consider environmental issues from a socio-political perspective.

"I always thought I was really interested in the politics behind international relations and diplomacy, and I thought the environment was totally separate from that," says Lauren Maunus ‘19, who decided to concentrate in Environmental Studies after taking King's course. "Coming into ES 11, that was the first time I made the connection that the environment is the most fundamentally global issue."

"There are some courses at Brown that teach you how to think—and not only make you think about problems, but change how you think about thinking about those problems," adds Brendan George ‘18. "This for me is one of those classes. It teaches you that there is no one environmental framework and that these issues are so interdisciplinary. If we're talking about water issues or transportation issues, there's no way you can leave out energy issues and food issues. These things all interact with each other."

"And then add on the fact that you have everyone in the classroom who's coming from a different angle and a different concentration and background," he continues. "It's just an eye-opening class. I think it opens people's minds."

The TAs are careful to note that ES 11 would not be what it is today without King's influence.

"While she makes it so accessible and so interesting, she also really centers the intersections of race and class and gender in the environment," says Logan Dreher ‘19. "That's not something that other environmental teachers always do. She really presents it in this political and social dimension."

Students who act as TAs for ES 11 do so out of profound gratitude and respect for the experiences they had as students in the class. For many, the course shaped not only their academic trajectory, but also their relationships to the world outside the University.

"It really helped all of us navigate our time both here at Brown and in the greater Providence community," concludes Masunaga Goto. "It has truly helped define my college experience, and I think that's something that this class offers that isn't true of all courses. It's empowering, and that's why it's so unique."