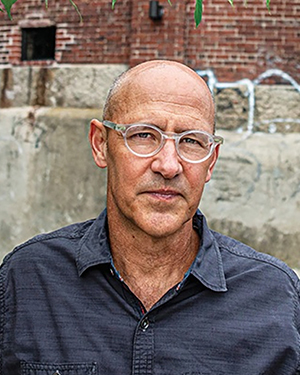

Professor of IBES and Sociology Scott Frickel recently released his latest book, Residues: Thinking Through Che mical Environments.

mical Environments.

Born in part from an IBES seed grant, the 200-page work offers “a new theoretical framework for understanding chemicals in society,” says Frickel, who studies the interactions between natural and social systems.

Frickel notes that much of the current social science research categorizes chemicals, whether by molecular structure or where they’re found (e.g. in the air, on land, or in the water). Residues, however, challenges this way of thinking.

“That’s not the way chemicals exist in the world,” Frickel states. “So we attach certain kinds of properties – social properties – to residues, to help guide ourselves and others into a different way of studying this problem.”

These properties include “irreversibility” (there can never be a world without chemical residues), “slipperiness” (residues often elude containment), and “unruliness” (residues interact with each other and the natural world in complex, unpredictable ways).

The book investigates how residues persist over time, how chemicals move through space, and how people understand and perceive residues, whether through instruments of measurement or anxieties about contamination.

“And then at the end, we bundle all of this up into an analytical perspective that we are offering to the world, to our communities, as a new way of thinking about this issue,” Frickel says.

And the book’s content is not its only innovative aspect: Residues was collaboratively authored by seven individuals.

“It’s an interdisciplinary group of scholars,” Frickel says of Soraya Boudia, Angela Creager, Emmanuel Henry, Nathalie Jas, Carsten Reinhardt, and Jody Roberts. They are sociologists, historians, political scientists, and science and technology scholars from America, France and Germany – all with work focusing, in some way or another, on chemicals.

“We thought it would be fun and interesting to pool our different kinds of knowledge on a general topic and see what we could produce together,” recalls Frickel. “And I think it reads nicely. It’s supposed to read like one person wrote the book.”

Frickel also notes the distinctiveness of the book’s cover, which depicts Georges Lemmen’s painting, Factories on the Thames. “We thought that its pointillist style did a nice job of evoking this notion of residues, which are both tiny and ubiquitous, voluminous and yet invisible.”

Now that the book is out, Frickel is excited to use its ideas to shape his future work, and he hopes others will do the same.