An interview with the Brown University undergraduate researchers who worked on Breathe Providence this summer.

Grace, Liv, Vasu, and Meg step outside of the Urban Environmental Lab on a cloudless July afternoon. They are four of the core members of Breathe Providence: a research study led by IBES and DEEPS Professor Meredith Hastings. The project aims to characterize Providence air quality on a hyperlocal level by setting up sensors across the city. For a brief interlude between work sessions, the team discusses the specifics of the project, their visions for the future, and more.

______________________________________________________________________________

Introductions

Grace Berg graduated from Brown in 2021 with an Sc.B in Geology-Biology. She’s the project coordinator for Breathe Providence—or as she describes it, Meredith’s “right-hand person.” She’s been working on siting the sensors, interfacing with community groups, and keeping track of the project’s various moving parts, as well as helping with financial and grant reporting work.

Liv McClain, class of ’22.5, studies Environmental Science on the Air, Climate, and Energy Track. She has been working on interviewing community members in order to add a narrative aspect to the team’s data. She has also been assisting with sensor-siting and general planning for how to execute the project.

Vasu Jayanthi, class of ’23, studies Environmental Science on ACE Track. Her efforts are focused on community engagement, environmental justice, and youth education. She’s working with the Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences’ youth outreach program, DEEPS CORES, to implement some of the project’s guiding scientific principles into the curriculum that they’re working on with Hope High School.

Meg Fay, class of ’23, studies Chemistry and Environmental Science on ACE Track. Meg has been working directly with the air quality sensors: getting them online, writing their code, retrieving their data, and interpreting the data to make it useful.

______________________________________________________________________________

The Project

What are you aiming to do with this project and how are you going to accomplish your goals?

Grace: Breathe Providence is something called a hyperlocal monitoring network. Hyperlocal means that we have really dense spatial resolution. In our case, we’re hoping to characterize air quality and natural gasses at a neighborhood scale—that’s within two kilometers or less—using lower-cost equipment.

Historically, this kind of monitoring has been really difficult due to how expensive sensors are. The EPA requires state agencies to operate reference-grade monitors that are many thousands of dollars, so it makes sense that they wouldn’t have the resources to do the level of monitoring we’re hoping to do. So at the bare minimum, our goal with this project is to characterize the heterogeneity of air quality and greenhouse gas pollutants in Providence at a fine scale.

One of the most important aspects of this project is that we are creating data that is relevant and useful to residents and policymakers. And that is something that a lot of our initial stages of the project have been trying to work on—creating relationships with state and city agencies like the Department of Health, the Department of Environmental Management, and the Office of Sustainability in the City of Providence. We also want to connect with community groups like the Racial and Environmental Justice Committee, the different health equity zones throughout the city, as well as neighborhood associations. And we’re working with these folks to find out where to site the sensors and how to engage community members in working with the data, in raising awareness about air quality and related health outcomes, and basically trying to make it so it’s not just research that goes into the void. This is something that can actually, hopefully, catalyze change, in particular towards environmental justice and greenhouse gas reduction.

Meg: Vasu and I are working on this project as our senior theses, so we have some more specific goals that relate to the branch of the project that we’re working on. Something that I’ve been finding really exciting is that, because it’s such a high density network with high temporal and spatial resolution, the end goal for me is to create an analysis of the city that shows neighborhood-scale production and transport, and potentially identify discrepancies between where pollutants are produced and where we’re seeing the effects of them.

Where does your funding come from?

Grace: Our grant comes through the Clean Air Fund. It’s an organization that’s supporting a lot of clean air work around the world. One of our precedents for this project is the Breathe London project, which has done awesome work in supporting the city’s Ultra-Low Emissions Zone work.

What pollutants are you monitoring?

Grace: We’re doing carbon monoxide (CO), carbon dioxide (CO2), NO and NO2 (NOx), three kinds of particulate matter (PM10, PM2.5, and PM1, but we probably won’t use PM1), and ozone.

Meg: With all of that, we’re also measuring meteorological conditions because all of these pollutants behave differently in different weather conditions. So part of the project and the calibrations is correcting all of the data so that they are comparable, which is going to be super important when we’re doing comparative studies.

Grace: We have pretty well spatially resolved data on health endpoints, like respiratory issues, and we have rates by census block group for child asthma and adult asthma. But we really just don’t have anything on the same level in terms of air quality data, so that’s something we’re hoping to be able to match. We’ll see if we’re able to identify a connection between ambient air quality and asthma attacks and asthma rates. Providence has some of the highest rates of child asthma in the country, and it’s starkly different based on neighborhood.

Where will the monitors go?

Grace: We haven’t distributed sensors to our physical locations yet. We have gotten explicit approval for three that are outside of our reference site at the moment, and we’re hoping to have all the sensors deployed by the end of August.

We have 25 sensors total and we’ll be putting them all over Providence, but concentrating more in the areas of South and Central Providence. These are the places that really have a higher density of [pollution] sources and that have notably higher asthma rates. And at our sites, there’s been a real environmental burden on these folks, and it’s that idea that we’re really hoping to tap into as well.

Meg: Right now as a part of the calibration efforts, we also have some of our sensors co-located with DEM’s operating network at Myron J. Francis Elementary School, and they’ve been collecting about a week or so of our first real outdoor data, which is super exciting.

When you get the data, what does it look like? What do you do with it?

Meg: When the data comes in, it comes in as CSV sheets, which are just pages and pages of unlabelled numbers and sometimes null values. So it is…completely useless to the average person and community upon arrival. So part of the project is taking these lists and lists of numbers and assigning meaning to all of them—calibrating them using the meteorological data. And then those get returned within a couple hours as graphs that show changing qualities over time. And then we’re hoping to create an even more user-friendly website, specifically for Providence, which will hopefully have some mapped data where people can see at what locations we have sensors set up and what the sensors are seeing.

What is the project’s connection with U.C. Berkeley?

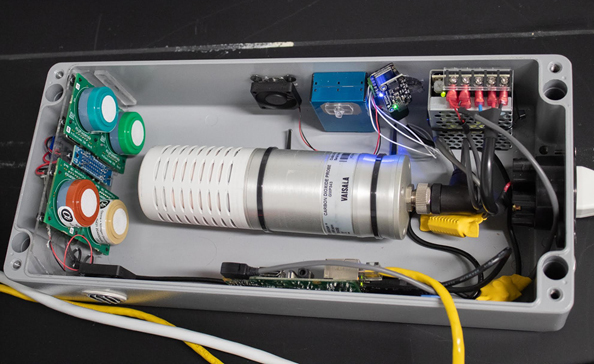

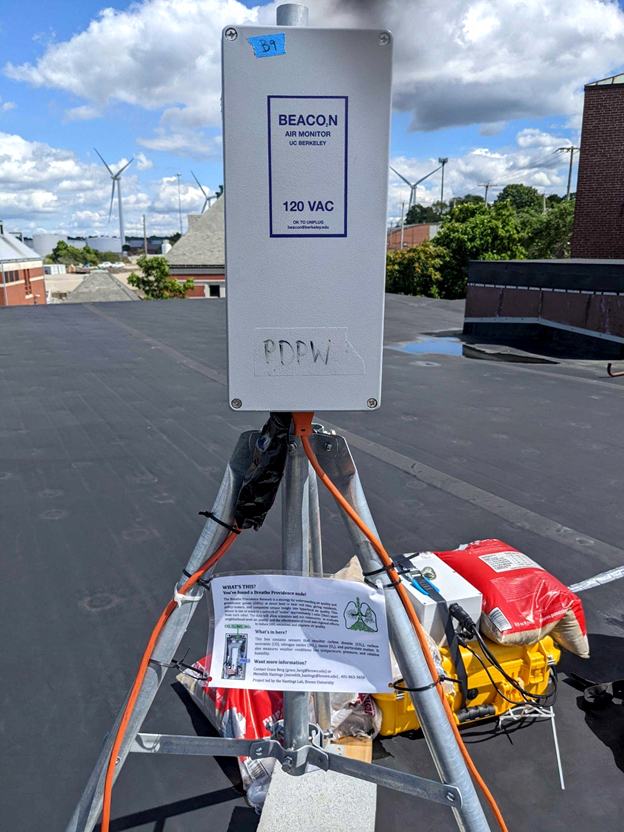

Meg: U.C. Berkeley has a high-density air quality monitoring network set up in the Bay Area called BEACO2N [the Berkeley Environmental Air-quality & CO2 Network], and the sensors that we’re using are technology developed from the Berkeley team called BEACO2N nodes. So the 25 nodes that will make up our network are BEACO2N’s boxes. They’re about the size of a shoebox and they have sensors for CO2 and pollutants like particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide, ozone, all that stuff. Our partnership with them involved coordinating us receiving some sensors to get our hyperlocal monitoring project on the ground, and then also getting an idea of how they chose their site locations and how they calibrated their data. That being said, they implemented their nodes at school locations, and we’ve taken a lot of this summer getting community input and site information on where our sensors are going to be deployed while we’re getting the math ready to do the calibrations. And whenever a stumbling block occurs, the research team at Berkeley has been very supportive for helping us solve these problems.

______________________________________________________________________________

The Team

How did you all end up on this team? What made you excited to be a part of the project?

Vasu: Meredith approached me about the project last October. She was just getting it off the ground running at that point, and she was interested in hearing about my experience with DEM because she was looking to partner with them. I was an intern with them last summer, so when she was describing the project to me and describing some of the environmental justice goals and goals for community engagement, I got really excited. And being able to equip the residents of Providence with this data seemed like a very, very important objective to me and something that I definitely wanted to be a part of.

Liv: My interest in air pollution in Providence is pretty rooted in environmental justice organizing work with Sunrise and some other organizations. I’ve always found the Port of Providence pretty fascinating—like, why is such a huge industrial center right inside of a really dense city? And obviously there’s pretty intense asthma disparities and environmental justice issues in this area. So I reached out to Meredith to do an independent capstone about air pollution. I was mainly doing a photography project of what’s actually in the Port, and then reading a lot of the history of organizing around air pollution issues in Providence—and then I stayed on to work on this project over the summer.

Meg: I joined the team in January 2022. For an Environmental Research Methods class, I ended up reading a lot of Meredith’s work on nitrogen transport, which was on the global scale. I decided to email her saying, “I’m really interested in pollutant transport on the global scale,” and she said, “Imagine if I had a project you could work on…on the smallest, most detailed scale that has been done to date.” And it sounded really interesting, so that’s how I joined the project on the research end of it.

Grace: As an undergraduate, I became particularly interested in environmental geochemistry, thinking about air, water, and soil quality. I became really interested in urban areas because they’re such centers of people. I wondered, how are pollutants affecting people? How are people producing these pollutants? And how is environmental contamination linked with climate change? I took Meredith’s Air Pollution and Chemistry class and I was in her research group. And my senior thesis work was, in large part, attempting to lay the groundwork for what we’re doing now. I was researching existing hyperlocal monitoring networks to basically gauge the efficacy of those types of networks versus more sparse government-operated networks, and using the pandemic as a case study because of the traffic reductions that happened. So that was really fascinating, and as I graduated, it seemed like there might be some momentum behind it in the way of funding. And so a year later, I ended up coming back here and joining the team.

What has it been like to conduct this research? How has it influenced your vision for the future?

Meg: Previously when I’ve done research, it’s been just bench research—I’m at the lab bench, I’m mixing two solutions, putting it under a microscope, that whole deal. And I feel like getting into field research and community-based research has been really eye-opening, in that you’re going to see the impacts of the science that you’re doing, and your motivation builds when you meet with community members. It’s also been super engaging for me personally to get out there and see science in action instead of just on a computer.

Grace: I think one of the most significant things about this project for me is the opportunity we have here to really transform and deepen the way that Brown interacts with Providence. And what we’re doing here, in my mind, is one of the most important things we could possibly be doing. And it’s so exciting and inspiring to get to meet with actors in this community who are dedicating their lives to helping make this a healthier, better place to live. We can have a partnership where we’re exchanging knowledge, expertise, and hopes, and it just feels so good to be a part of that.

Vasu: I’ll echo what Meg and Grace said—it’s so important for us as Brown students to understand where we are and understand our position of privilege, and to use that to actually support the community that we get to be a part of. Part of it for me, with what I’ve been working on with DEEPS CORES, is trying to build an infrastructure that’s gonna last even after I leave this place. I think that’s something that’s reflected throughout the team and throughout the project: we really do want to make a lasting impact on people that will support them for a long time to come.

Meg: Something we’ve all said, and also heard from community members, is that it’s nice to be off of College Hill. People have said, “Oh, you’re from Brown? It’s nice to see you out here.” And you realize that you haven’t been engaging with the entirety of Providence until you start doing that.

Liv: I’d say that this has been an enlightening experience in marrying environmental justice and data. I just think that together as a team, we bring so many different perspectives, and putting those all together, versus if this was solely a data project or if we didn’t have Vasu reaching out to young people and engaging them—it’s just so well-rounded. Data can only go so far if it’s not actually rooted in the community. It’s also amazing to see these incredible groups like the People’s Port Authority and Sunrise Providence: there are all of these groups who have been out there doing the work and protesting. So I just want to shout them out, too, for inspiring us.

What’s it like to work in an all non-male group?

All: We have Wendell!

Meg: Wendell Walters is an IBES research professor who has been immensely helpful when it comes to writing calibration scripts. A lot of the work is being done in a programming language that I’ve never used before and he has been really patient, sitting with me working on that, and also going out to our reference site with me to collect data. Real world data is messy and requires a lot of work—it’s something I haven’t had experience with before, and Wendell has been so supremely helpful. That being said, he is our token man! So other than that, I think it’s really refreshing to work in a group of women.

Grace: I love it. Especially because Meredith is really involved with women in STEM, it’s awesome to have her as a mentor and also know that she’s working towards broad institutional change.

Liv: Yeah, she’s done a lot of work with an organization called the Earth Science Women’s Network. I also think it’s exciting even in the big lab group meetings that we have. Meredith talks to one of our co-workers about her baby and she even brings the baby to the meeting. It’s just something I’ve never seen in the workplace before: seeing someone, particularly in a parental sense, as more than their job. It’s really inspiring to see there are different ways to be a woman in academia.

___________________________________________________

Lily Lustig is a senior at Brown concentrating in English and Environmental Studies on the Land, Water, and Food Security track. She has written articles as an IBES Communications Intern since February 2021.