Environmental pollution may have shaped the formation of racially segregated neighborhoods, a study by Brown Ph.D. candidate Jonathan Tollefson suggests.

For years, researchers have understood that there is a complex relationship between pollution and segregation in cities. But most research on environmental inequality utilizes data from after the 1980s, when racial segregation was already firmly established as a neighborhood-level phenomenon.

“That’s a relatively recent structure,” said Tollefson (who uses they/he pronouns), noting that segregation was once primarily seen on a street level. “Urban sociologists haven’t been able to understand how the environment shaped segregation when it was first established in the early 20th century as this pattern of large, contiguous, homogeneous neighborhoods,” they added.

Archival data unlocks new perspectives

Tollefson’s working paper, “Environmental risk and the reorganization of urban inequality in the late 19th and early 20th century,” aims to address this knowledge gap.

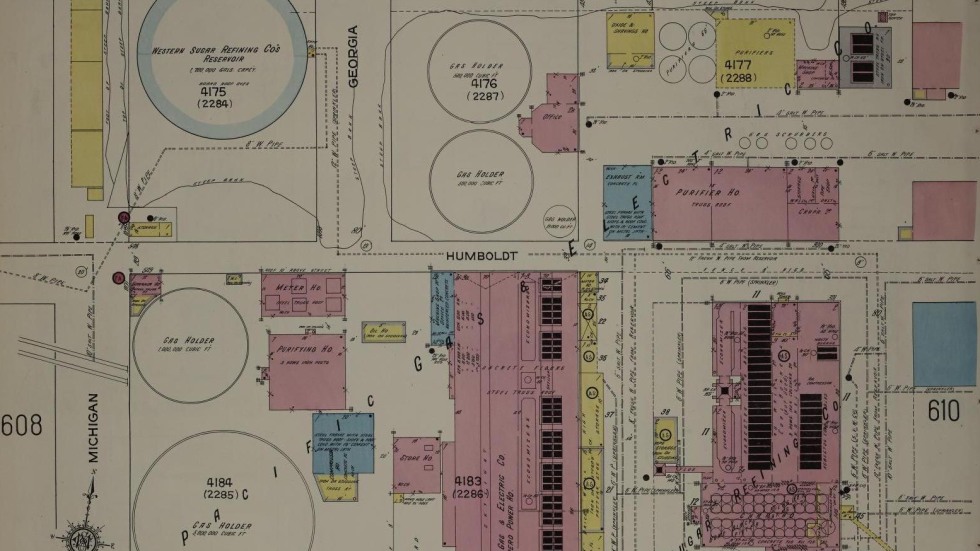

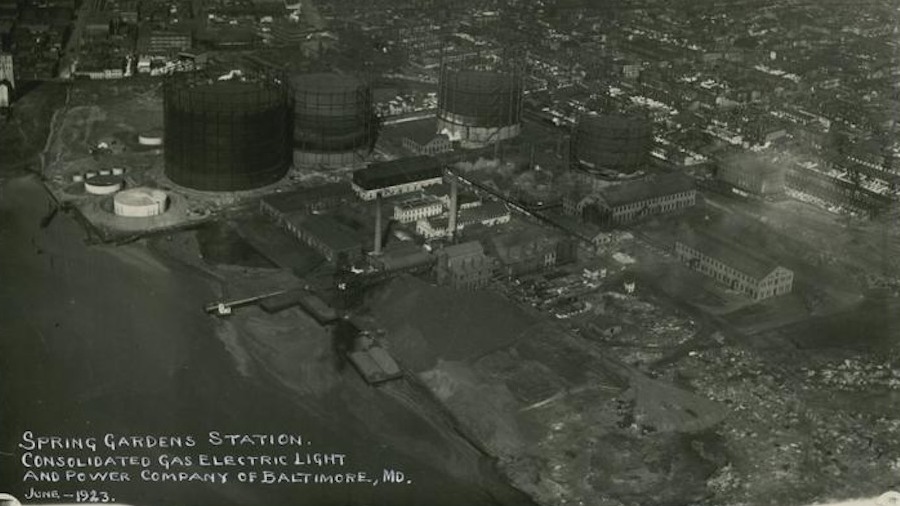

The study centers upon seven cities — Baltimore, Cleveland, Minneapolis, New Orleans, San Francisco, Oakland, and Providence — and focuses on the manufacturing gas industry, one of the “first urban fossil fuel utilities” and a “major source of environmental pollution that people at the time recognized as being really important to how cities were structured,” Tollefson said.

Using census data and historical maps to locate industrial sites, Tollefson was able to elucidate how personal demographics were linked to the proximity of industry.